Die Schlacht von Gallipoli 1915

Die deutsche Beteiligung

Defence Preparations of the Dardanelles

Continue in German

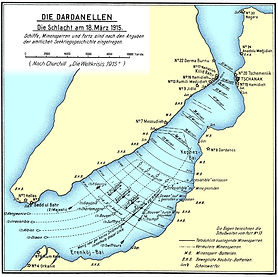

The Dardanelles disposed of historical, ancient fortifications. However, the extension of the works had not kept pace with the progress of technology. The main focus lay in the defence of the straits against a naval attack from the west.

The main fortifications were on both shores of the Dardanelles, where there were coastal batteries and forts whose main effect was aimed towards the Aegean Sea. A fleet that broke through this barrier could fire from the rear and against an attack from the landward side these fortresses were practically defenceless. As early as 1836, Helmuth von Moltke wrote about the historical use of the Dardanelles fortifications after his visit to Çanakkale: „Some daring and lucky maritime enterprises of the English have spread the general view that land batteries cannot defend against fleets, which are of course superior in the number of the guns. Such an enterprise was that of Lord Duckworth in 1807. At that time the defence of the Dardanelles were in the most pitiful state; the English squadron sailed by, almost without finding opposition [...] If the artillery is organized in the Dardanelles, I do not think that any hostile fleet of the world might dare to sail through the straits; one would always be obliged to disembark troops and attack the batteries at the narrrows“(i).

The fortification of the narrows consisted of two groups. A forward group was formed by two batteries on the Asian side with Kumkale (Fort Orhanié) and on the European shore with Seddil Bahr. These batteries included a total of 20 guns of various calibres from 15 to 28 cm, old models without rapid-fire devices and with short range, apart from four guns with a range of just 15 km. The main fortifications were formed around a group in the vicinity of Çanak - Kilid Bahr – Cape Kilia – Nagara (ii). Only near Cape Kephes on the Asian shore was there a medium forward battery. Altogether there were about 80 guns of the most disparate kinds available which hardly corresponded to the demands of a effective coastal defence against modern warships. Moreover, the construction of the fortifications was not up to date. The facilities dated mostly from the Russian-Turkish war of 1877/78 and were either brick walls or just earthworks. The batteries were open and there was neither armoured protection nor concrete. The guns were almost exclusively of German manufacture (Krupp) and their delivery could still take place until mid-1914 by sea from Germany. The installation of the heavy cannons under the direction of German experts required great expenditure and some forts were constructed round the weapons. Admiral Souchon judged, after rumours of an allied naval attack grew at the end of 1914: „ I do not think that the English and French will force the Dardanelles, because they are not able to decide between themselves who should pay the price with Dreadnoughts. So many good mines lie in the long, sinuous passage and so many cannons and soldiers stand on both shores that the attacker must count on a major operation in all circumstances. Even if, after appropriate losses, he then gets some ships through into the Marmara Sea, he can undertake nothing significant further unless he can establish himself on the shore with the help of substantial landing forces “ (iii). He thus agreed with the evaluation of General Liman von Sanders who ascertained similarly: „Hence, a crucial success could be achieved by the enemy only if a large troop landing against the Dardanelles will be sycnhronised with the breakthrough of the fleet or would take place ahead of this. A troop landing only following the breakthrough would not have the support of the artillery of the fleet that had already broken through. “ (iv).

Until the takeover of responsibility by the German officers in 1914 the fortifications of the Dardanelles had been completely neglected by the Turkish side, at least according to the judgment of German experts. This deficit had been recognised early by General von Sanders and he wanted to take over responsibility for these defensive arrangements, although they were still subordinate to the area of responsibility of the British naval mission. Nevertheless, the "Limpus mission" was held even by the Turkish side as incapable of fulfilling this duty ; it was pejoratively called "ridiculous", Admiral Limpus was estimated as a „weak and soft character“ and the German military mission was considered in comparison to the British as of "towering" superiority (v). Enver welcomed the intention to put the fortifications under German responsibility. For that reason a German naval officer should be ordered as a matter of camouflage first to the army and later moved to Istanbul to join the military mission. This expert for coastal fortifications was assigned to General Weber, the Chief of Staff of the Turkish engineer and pioneer corps. With this measure the Germans wanted to gain access to the fortifications but also ensure deliveries by German industry. Nevertheless, this intention was not effected immediately, because Admiral Souchon noted on 27th August, 1914 in the war diary of the MMD: “The forts have still mostly never fired a shot. Absolutely unclear ideas over fire control. The deployed mines lie for the most part 70 or 80 metres displaced and can apparently lie no longer than four weeks with certainty in the same place “ (vi). One day earlier, Ambassador von Wangenheim had informed the Foreign Office that he only could support an attack towards the Black Sea if the Dardanelles had been protected (vii). The command and control at the Dardanelles was not clearly regulated and was split into different areas of responsibility. Admiral von Usedom had taken over the command of the fortifications of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus in September 1914. As a delegate of the Turkish headquarters and with direct responsibility to Enver Paşa, there was, in addition, Admiral Merten in Çanakkale. Nevertheless, the commander of the fortress on the Dardanelles was the Turkish colonel Cevad Bey. To him were subordinate all troops of the coastal defence in the southern part of the Gallipoli peninsula. Admiral von Usedom reported on the 5th June 1915 about the command and control structures there and the intention regarding how to optimise them: „The command structure of the fortifications could not be organised as it should be militarily, because of the somehow strange evolution of the local circumstances. Now I held that the time had come to centralise the organisation more and achieved first that both strait fortresses – as far as it also concerns warfare and defensive measures – were subordinated directly to me as „governor general of the straits“, while I remained affiliated to the Main Headquarters. This new position corresponds to that of an army commande. When on 24th of April indications signs increased that pointed to renewed hostile enterprise against the Dardanelles, the Minister of War on 25th April transferred to me the direct command of about land and sea forces in the Dardanelles fortress area, while I agreed at the same time with the head of your Majesty’s Mediterranean Division in his position as a Turkish naval commander that elements of the fleet should also be subordinate to me, as long as they stayed in the fortress area that, however, authority for allocation and withdrawal of these elements remains with the naval commander“ (viii).

Most of the German officers and teams who came from the MMD or the Sonderkommando (SoKo) were deployed to the fortifications, regarding which Admiral von Usedom proudly commented „despite the recognition of the purely German character of the troops subordinated to me, I succeeded in taking over the most important batteries in both straits with them; Turkish soldiers are used in these batteries only as ‘auxiliary numbers’ and reserves“ (ix). For example Lieutenant-Commander Wossidlo took command of the Hamidiè fort to the south of Çanakkale with its 35.5 cm guns. The approximately 170 remaining Germans worked together with the Turkish crews of the fortifications and essentially provided the training of the teams. The mobile artillery, which was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Wehrle undertook an important portion of the defence of the straits. Wehrle was a commander of No 8 Heavy Field Artillery Regiment and had moved with his troops, including a training battalion, in September 1914 to the Dardanelles. The heavy field artillery batteries, which had been distributed to both shores, were to conduct the defence against ships penetrating into the Dardanelles from constantly varying positions, as well as to monitor the sea minefields against clearing. Firing and alert exercises as well as signal service and supply had been practised till then only very insufficiently. About the state of the gun crews and the weapons Wehrle wrote: „Soon after its institution the training battalion fired in the presence of the Marshal [Liman von Sanders] from a concealed position against a drifting target. Because of the lack of practice and suitable aiming procedures the result was exceedingly pitiful. I explained the reasons to the very disappointed and angry Commander-in-Chief and assured him that firing procedures would be practised that exclude such failure. I was firmly determined to have all batteries fire against moving targets; nevertheless, everything was missing to be able to carry out a simple procedure based on precise measurements, as required for coastal firing “ (x).

After that Lieutenant-Colonel Wehrle set up temporary aiming mechanisms made of oak and practised firing at moving targets as well as rapid re-positioning of the light guns. He wrote: „I can touch on the following period, which was equally strenuous for the regiment and me, quite briefly. Every day brought new disappointments and bit by bit I recognised that we had to start completely from the ground up. All German concepts of the independence of the junior commanders melted away; from the simple gunner up to the battalion commander there was no duty which did not have to be demonstrated or done by oneself. The constant fight against unpunctuality, sluggishness, deceit and abuse of official power could only be dealt with by means of the most austere punishment“ (xi) . However, in a report of Admiral von Usedom on the 18th December 1914 the first results could be reported to Berlin: „The training of the Turkish artillery teams in the coastal facilities has continued and has produced rather good results. The last firing exercises in both straits proved not only considerable progress in the results, but also in the management of the batteries by the Turkish officers, of whom a larger number has turned out to be trainable than was previously assumed“ (xii). He further explained appreciatively: „The torpedo lieutenant-commander Gehl, who is commanded to the Special Command and operates here as a major of Engineers, has done very well in re-manufacturing old mines and has understood very well how to find and use existing material, which was unknown to the Turkish officers.“ In addition, numerous false positions were built to deflect hostile fire. US Ambassador Morgenthau, who had visited the Dardanelles at the invitation of the Germans, described the implementation of this idea: „South of Erenkeui, on the hills bordering the road the Germans had introduced an innovation. They had found several Krupp howitzers left over from the Bulgarian war and had installed them on concrete foundations. Each battery had four or five of these emplacements so that, as I approached them, I found several substantial bases that apparently had no guns. I was mystified further at the sight of a herd of buffaloes---I think I counted sixteen engaged in the operation---hauling one of these howitzers from one emplacement to another. This, it seems, was part of the plan of defence. As soon as the falling shells indicated that the fleet had found the range, the howitzer would be moved, with the aid of buffalo-teams, to another concrete emplacement. "We have an even better trick than that," remarked one of the officers. They called out a sergeant, and recounted his achievement. This soldier was the custodian of a contraption which, at a distance, looked like a real gun, but which, when I examined it near at hand, was apparently an elongated section of sewer pipe. Behind a hill, entirely hidden from the fleet, was placed the gun with which this sergeant cooperated. The two were connected by telephone. When the command came to fire, the gunner in charge of the howitzer would discharge his shell, while the man in charge of the sewer pipe would burn several pounds of black powder and send forth a conspicuous cloud of inky smoke. Not unnaturally the Englishmen and Frenchmen on the ships would assume that the shells speeding in their direction came from the visible smoke cloud and would proceed to centre all their attention upon that spot.” (xiii) . About his meeting with Wehrle wrote the American Ambassador: „The first fortification I visited was that of Anadolu Hamidié (that is, Asiatic Hamidié) located on the water's edge just outside of Tchanak. My first impression was that I was in Germany. The officers were practically all Germans and everywhere Germans were building buttresses with sacks of sand and in other ways strengthening the emplacements. Here German, not Turkish, was the language heard on every side. Colonel Wehrle, who conducted me over these batteries, took the greatest delight in showing them. He had the simple pride of the artist in his work, and told me of the happiness that had come into his days when Germany had at last found herself at war. All his life, he said, he had spent in military exercises, and, like most Germans, he had become tired of manoeuvres, sham battles, and other forms of mock hostilities. Yet he was approaching fifty, he had become a colonel, and he was fearful that his career would end without actual military experience.” (xiv)

A clearly limiting factor in the defence of the Dardanelles were the limited ammunitions stocks. This was caused on the one hand by insufficient organisation of the logistics but also because of the restricted opportunities to manufacture large-calibre ammunition in Turkey. Because there was at that time no secure land connection via friendly nations, support could hardly be given from the German war industry. New aiming and signal technology were procured from Germany and smuggled through Bulgaria and Romania into Turkey. About the transport of this ammunition and ammunition parts von Schoen wrote: „The most ingenious means had to be taken to bring ammunition and technical instruments ‘from the rear’ through Romania. In cement blocks for the ‘construction of the Baghdad road’ machine guns were hidden, breech blocks and spare parts rested on the bottom of barrels filled with oil, many freight wagons had double walls in which many useful things could be stowed away“ (xv). All supplies of artillery ammunition as well as means of maritime warfare available in Turkey were sent to the Dardanelles. Among them were also 26 Carbonit-sea mines which had come via devious ways from Germany. These mines were to play a critical role in the coming battle - they were used by the mine layer Nusret for the historical minebarrier. The Mediterranean Division provided not only staff, but also ships’ guns, which were broken down for this purpose in the shipyard of Istinye, shipped in smaller boats to the Dardanelles and then inserted in the gun positions. On 2nd March 1915, Admiral Souchon was sending two 8.8cm guns with ammunition, on 9th March, 200 shells of 15cm ammunition, on 16th and 20th March 12 mines and later two 15cm guns of the GOEBEN to the Dardanelles (xvi). In addition, the sea-mine barriers and the torpedo battery at Kilid Bahr under the professional management of Corvette Captain a. D. Gehl could clearly be improved (xvii).

In this situation it was a piece of luck that the former commander of the cruiser YORCK, Captain Pieper, had been moved to the MMD. He had had been accused of responsibility for the loss of the YORCK in the North Sea close to Wilhelmshaven and with it for the death of 336 sailors. So he had been sentenced to fortress custody but got the chance of probation in war to escape the fortress custody. Hence, he had come with pleasure in Turkey to make put this incident behind him. Souchon wrote in addition: “I have put a great deal of effort into ensuring that the unlucky YORCK commander, Captain Pieper comes here for the fortifications. The start of his sentence will be suspended until the end of the war. He is an experienced artillery specialist and will be able to rehabilitate himself in the Dardanelles fortifications“(xviii). After Admiral von Usedom did not want to have Captain Pieper at the Dardanelles for personal reasons, Souchon was able to convince Enver Paşa to use Captain Pieper as the head of the Turkish weapon office. In this function he performed astonishingly well and decisively and in the shortest time improved the quality and amount of the ammunition production from the different munitions factories in Istanbul. Now even von Usedom, who had rejected him first as a staff officer in his own staff, found laudatory words for his achievements and reported: „Captain Pieper devotes himself to his service with great devotion, even if new supplies have not yet reached the frontline, by adjusting available supplies and has ensured the continuation of the battle“ (xix). About the successful fights on the Gallipoli peninsula he even judged: „I do not go too far to go if I suggest that without the achievement of Captain Pieper and his organisation the attacks of the enemy on the Gallipoli peninsula could not have been beaten off in the long run“ (xx).

Captain Pieper who now held the rank of a Turkish major general, summarised the work of the weapons and ammunition inspection subordinated to him in a detailed report of 25th January 1916 as follows: „In this respect an excellent cooperation with German spirit has arisen, which is felt here with particular joy and which has not been affected by the smallest difference. Elsewhere in this report it was explained how the quality of the ammunition was made the object of special care and control. In this respect the contribution of the explosives officers was particularly valuable, who have proved themselves very well in inspection, mixture and largely also construction“(xxi). In his report Pieper described the difficulties of the raw material supply and enlargement of the production plants for ammunition. For that reason requisitioned facilities from occupied areas had been put in place and German-speaking experts in metal processing had been employed. These had already been active in Turkey and could now train the increasing number of Turkish workers. However, his report also contained a detailed list of the personnel in his department from which it emerges that all divisions were headed by German officers and also many experts such as explosives-maker were involved in sergeant's ranks in the production. Altogether there had been 74 professional officers, officials, engineers, chemists, 47 handcraft masters and 659 workers from Germany who trained and supported the more than 14,000 workers in all armament companies. Shells of calibres 7.5cm to 21cm were produced and fuse production was undertaken for 21 different kinds of shells. The raw materials for the shell factories came partially from the railway workshops; however, shell fragments were also collected from the battlefield and re-melted. Gunpowder had to be produced and for testing weapons and ammunition a firing range was established close to Istanbul. In addition, new weapons, i.e. guns, means for fire control, close combat means, like rockets, handle shells, mines and bomb throwers were produced, which were mainly used from summer 1915 in the battle for Gallipoli (xxii).

Nevertheless, owing to the high ammunition consumption by the continuing employment of the artillery there were still bottlenecks in the ammunition supply for the Gallipoli battlefield. Thus telegraphed Ambassador von Wangenheim on 1st July 1915 to Berlin: „General Pieper, organizer of the Turkish ammunition manufacturing, told me that if 400-450 wagonloads of ammunition could be sent here immediately, it would help him to sustain supplies for the critical time of about one month, needed to bring the manufacture up to the necessary level for the effective defence of the Dardanelles“ (xxiii). At last the work by Captain Pieper was appreciated so highly, that on 8th December 1915 Emperor Wilhelm II, in recognition of his excellent merits in connection with the weapon business and particularly for ammunition manufacture in Turkey, which has contributed substantially to the previous results of the allied Turkish armed forces, released him under pardon from his punishment of fortress custody from 28th December 1914 (xxiv).

[i] Moltke, Briefe, S. 100

[ii] Mühlmann, Schlachten des Weltkrieges, Bd. 16 Der Kmpf um die Dardanellen, S. 50

[iii] Langensiepen, Halbmond und Kaiseradler, S. 103

[iv] Sanders, Fünf Jahre Türkei, S. 65

[v] AA/PA, Türkei 142, R 13319, Militär-Bericht 5 vom 24. März 1914

[vi] BA/MA, RM 40 / 755, Kriegstagebuch der Mittelmeerdivision

[vii] Mühlmann, Das deutsch-türkische Waffenbündnis im Kriege, S. 21

[viii] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2404, Bericht Usedom 05.06.1915

[ix] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2355

[x] Wehrle, Aus meinem türkischen Tagebuch, S. 34

[xi] Wehrle, Aus meinem türkischen Tagebuch, S. 34

[xii] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2404

[xiii] Morgenthau, Kapitel XVIII

[xiv] Morgenthau, Kapitel XVII

[xv] Schoen, Die Hölle von Gallipoli, S. 18

[xvi] Lorey, Der Krieg in den türkischen Gewässern, S. 86

[xvii] Mühlmann, Schlachten des Weltkrieges, Bd. 16 Der Kampf um die Dardanellen, S. 52

[xviii] Langensiepen, Halbmond und Kaiseradler, S. 105

[xix] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2404, Bericht von Usedom, 5. Juni 1915

[xx] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2404, Bericht von Usedom, 31. Oktober 1915

[xxi] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2404, Bericht Kapitän Pieper

[xxii] Lorey, Der Krieg in den türkischen Gewässern, S. 387 ff

[xxiii] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2356

[xxiv] BA/MA, RM 5 / 2358